Shelley's Septic Tanks and GIPTA Violations

I've had a request for information relating to Shelley's Violations. You can click on the photos to see them more clearly. You can see their Consent Order with the FDEP here.

|

| Visit website |

- Shelley’s Septic Tank, Inc. (dba Shelley’s Environmental Systems):

- FDEP issued a Consent Order to Shelley’s on March 24, 2020 regarding wastewater permit violations that involve mainly odors, and National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) stormwater permit violations (multiple issues). The Order included penalties and fees of $8,712 and required the company to develop an odor plan as well as a plan to develop and implement stormwater best management practices within 60 days. Shelley’s was requested to respond within 20 days.

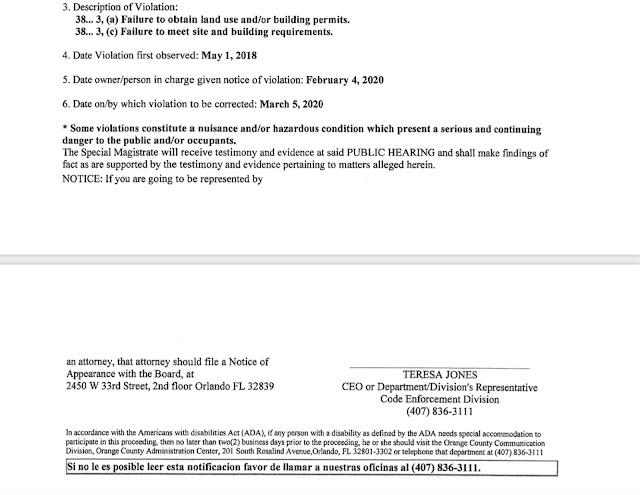

- Orange County’s Code Enforcement Division has issued a series of violation notices to Shelley’s. A March 5, 2020 compliance deadline regarding building permits and site requirements was not met. As a result, a Special Magistrate hearing has been scheduled for July 8, 2020 at the County Administration Building, First Floor, 201 S. Rosalind Ave., Orlando, 32801.

• Orange County’s Environmental Protection Division issued an Air Quality Non-compliance Letter on February 19, 2020 citing objectionable odors. An enforcement meeting between Orange County and Shelley’s is expected to occur by early May 2020.

GPITA, LLC:

GPITA, LLC:

- FDEP and GPITA agreed to (executed) a Consent Order on April 7, 2020 regarding yard trash. The Order included $1,000 in penalties and $250 for costs and expenses incurred during the investigation. GPITA has 180 days to remove or reduce the cited yard trash.

- EPD issued an Air Quality Non-compliance Letter on February 19, 2020 citing objectionable odors and requesting information outlining what measures will be implemented to prevent future reoccurrence. An enforcement meeting is expected to occur by early May 2020.

- Orange County Code Enforcement Division issued a Code Violation Notice on February 4, 2020 citing non-permitted uses. The violation notice indicated that applications for special exceptions should be submitted immediately. To date, a reply has not been received. A Special Magistrate hearing is scheduled for July 8, 2020 at the County Administration Building, First Floor, 201 S. Rosalind Ave., Orlando, 32801.

The copied and pasted articles below refer to violations in Shelley's Septic Tank's past. There was a court action after this but all references to it and the story of why Anuvia is next door to them are mysteriously missing from the internet. Curious...http://www.news-journalonline.com/news/local/flagler/2010/10/26/sludge-issue-raises-stink-in-bunnell.html

Sludge issue raises stink in BunnellBy JULIE MURPHYOctober 26, 2010BUNNELL — All sludge is not created equal.

There is sludge that is treated as required by law, first at the sewage-treatment plant and then, again, by the companies that haul it away and disperse it on designated sites across the state every day, without incident.

Then there is sludge that violates state law, the kind that was recently dumped on a Bunnell field, straight from the Daytona Beach treatment plant without any secondary treatment. It smells horrible and attracts swarms of flies, “ruining” the lives of nearby residents.

Under-treated sludge also creates conditions ripe for high levels of fecal coliform that could cause “a host of diseases” including E. coli, officials said. And, if a hard rain hits soon after it’s been spread, sludge runoff can contaminate nearby lakes or streams and groundwater.

The illegal dumping — which has happened before and agitated western Flagler County residents for years — led the state Department of Environmental Protection to send a “notice of permit denial” to Shelley’s Environmental Systems of Zellwood earlier this month. The company has until Thursday to file a petition for an administrative hearing or the DEP’s proposed action for denial would become final.

“Then it moves into the court system, and there’s no way to guess-timate how long it will take,” DEP spokeswoman Lisa Kelley said. “Until there’s a ruling, they can conduct business.”

That is, they can conduct business as long as they’re doing it properly, and Kelley said the company would be subject to criminal charges if it dumps under-treated sewage again.

“They, like all facilities, will be monitored closely,” she said.

According to its website, Shelley’s is “the industry leader in ‘biosolids (residuals) management,’ for over 25 years.” The permit denial by the DEP puts cities that contract with them — including Daytona Beach, Ormond Beach and New Smyrna Beach — in the position of possibly needing to find a new company quickly to haul away hundreds of tons of treated sewage each week.

Investigators from the DEP, with help from the state Department of Transportation, followed a Shelley’s truck Sept. 27 from the Daytona Water Treatment Facility on LPGA Boulevard to Cowart Ranch property off County Road 305 in western Flagler County, according to DEP reports. They witnessed Douglas “Bear” Shelley and Scott Matthew Roberts “dumping raw residual waste on spread fields.” Both men were charged with illegal dumping.

“This was not completely untreated waste,” Kelley said. “It was treated at the water-treatment facility, but it’s supposed to be further treated to reduce (fecal) coliform and vector attraction (flies).”

Dale Clegg’s family still has property near the Cowart Ranch, but he no longer lives across the street from where the dumping occurred.

“It was ruining our life,” he said. “The smell and the flies. I really couldn’t understand why they would do this to us.”

Clegg is one of many western Flagler County residents who kept after county and state officials to “do something” to keep the odor under control and the number of flies down. The DEP also found Shelley’s out of compliance in August 2007 and is in court with the company now over several inspection violations found in 2008, including improper discharge.

“I’ve seen them come out (to dump) on Thanksgiving, and then it just sits there piled up,” he said. “And then again on Christmas Eve, I tried to let my little girl enjoy the night and the full moon but had to bring her back inside.”

Done correctly, “bio-solids are the primary organic solid product yielded by municipal wastewater treatment processes that can be beneficially recycled,” according to the Environmental Protection Agency’s regulation documentation, commonly referred to as the “Part 503 rule.”

Lifelong Bunnell resident Blane Taylor said his concern is what happens to the surrounding soils and aquifer when a spread is done incorrectly.

There are “a host of diseases” associated with under-treated waste, according to Benjamin Juengst with the Flagler County Health Department.

“The most common are E. coli, shigella, giardia, cryptosporidium,” he said.

All four can cause severe diahrrea, whether by virus, bacteria or parasite.

Juengst said runoff is more of a problem than what could possibly seep through the ground to the aquifer, because sunshine would kill any viruses spread on the fields. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, though, there are some E. coli organisms that can survive several weeks on countertops and up to a year in materials like compost.

David Shelley, the owner of the company, has not returned repeated News-Journal calls, but Rob Cowart — a member of the family that owns Cowart Ranch — spoke freely.

“We don’t get paid to let them dump on the land,” he said while eating a large midday dinner at a long farm table in his kitchen wallpapered with cowboy boots. “But we don’t have to purchase fertilizer for our land. And, you know we have poor soil here in Florida.”

He doesn’t worry about living on the property — which is a stone’s throw from one of many spread fields — and his nephew Charlie Cowart jokes about playing in the “cake,” as the solid residuals are called.

“Besides,” the older Cowart said, “what are you going to do with it if you can’t put it on the property?”

The Sept. 27 dump in Bunnell was about 25 yards, or 2,000 pounds of partially treated sewage.

“Shelley’s is permitted to produce 283.8 dry tons per day for land application on agricultural sites in accordance with an approved agricultural use plan,” Kelley said.

There are 10 other “residuals management facilities” besides Shelley’s that work in the eight-county Central Florida region of Marion, Lake, Volusia, Seminole, Orange, Brevard, Osceola and Indian River counties. Kelley said there “has been no concern expressed” about whether the other facilities can handle the workload.

According to DEP records, Shelley’s dumps bio-solids it collects from Daytona Beach, Ormond Beach and New Smyrna Beach, as well as from several local RV resorts and motels, at eight sites in Volusia and Flagler counties totaling more than 3,900 acres.

In the past three years, Shelley’s Environmental is the only company of the 11 that serve the Central Florida region that has had violations egregious enough that the DEP had to step in and take action through “formal enforcement,” Kelley said.

Daytona Beach has had a waste-removal contract with Shelley’s since 2004. The company makes three pickups a day, every day, for a total of 323 tons each week at a cost of slightly more than $35 a ton, which adds up to $11,382 per week.

“We have contacted another hauler, Florida Enviro, who has a facility at the Tomoka Landfill, and they have indicated that they could haul, treat and dispose of our sludge on short notice,” Daytona Beach spokeswoman Susan Cerbone said Friday.

Other municipalities also are considering their options.

“We’re uncertain whether it will affect us,” said Ellen Fisher, spokeswoman with the Utilities Commission of New Smyrna Beach. “We’re a little different, because we already treat ours (to a level where it can be directly spread). We are looking at our options, though.”

http://www.news-journalonline.com/news/local/flagler/2010/09/30/contractors-face-charges-of-illegal-dumping.html

Contractors face charges of illegal dumping

September 30, 2010

BUNNELL — Two men who work for a bio-solids management company under contract with the city of Daytona Beach are accused of dumping untreated human waste in Bunnell.

Douglas “Bear” Shelley and Scott Matthew Roberts — both employed by Shelley’s Environmental Systems in Zellwood — were arrested Monday afternoon and charged with illegal dumping.

Investigators from the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, with help from the Department of Transportation, witnessed the men “dumping raw residual waste on spread fields without the required treatment,” according to a DEP report.

“The waste from this incident was ordered by DEP’s Central Regulatory District to be removed by Shelley’s when they came to remove the truck,” DEP spokeswoman Amy Graham said.

Investigators followed Roberts as he drove a Shelley’s truck from the Daytona Water Treatment Facility on LPGA Boulevard to Cowart Ranch property off County Road 305 in Flagler County.

“Once Mr. Roberts entered onto the Cowart Ranch, he dumped approximately 25 yards (2,000 pounds) of raw human waste onto the ground,” the report states.

The report notes “roughly 60 head of cattle” were about 150 feet from where the human waste was dumped, “leaving easy access for the cattle to come in direct contact with the waste.”

State law stipulates animals shouldn’t graze on land for 30 days after “Class B residuals (treated)” are applied.

Douglas Shelley reportedly admitted “to allowing cattle to remain on the field during the land application of residuals, which is also in violation of DEP permit,” according to the report.

“The cattle, therefore, were directly exposed to raw human waste, which contains microbes, parasites and viruses that could lead to the animals carrying disease-causing organisms that are harmful to humans,” the report states.

No one from Cowart Ranch could be reached for comment Wednesday.

Douglas Shelley, the field manager, “is responsible for the land application of the residual waste, and to ensure the waste had been properly treated before being land applied,” according to the report. Investigators said, “Mr. Shelley knew the waste was not treated, but still allowed the waste to be illegally dumped onto the permitted field.”

David Shelley, the company’s owner, declined to comment about the situation or say whether disciplinary action had been taken against his employees.

Daytona Beach spokeswoman Susan Cerbone confirmed the city has had a waste removal contract with Shelley’s since 2004. She said three pickups are made per day, every day, for a total of 323 tons each week at a cost of slightly more than $35 a ton, which adds up to $11,382 per week.

“The city of Daytona Beach contracts with Shelley to pick up the wastewater sludge from our LPGA facility, treat it and then dispose of it,” she said in an e-mail. “They are supposed to haul the sludge to their Zellwood facility for treatment. Apparently, they skipped the treating part.

“The city had no knowledge that they were doing anything other than what their contract states.”

Cerbone said the untreated sludge from the plant is considered the property of Shelley’s once it has been removed.

According to the company’s website, Shelley’s Environmental Systems has access to 400,000 acres in Osceola, Orange, Volusia, Seminole, Flagler, Sumter, Lake and Citrus counties. It has a fleet of more than 70 tankers and dump trailers and a storage capacity of 360,000 gallons of liquid and 1,500 wet tons of “dewatered residuals.”

In addition to the arrests of Douglas Shelley and Roberts, two of Shelley’s drivers were cited with six equipment violations, according to the DEP, and “DEP regulatory has opened a new civil case against Shelley’s resulting from the operation, and also has a currently pending civil case.”

Graham was unable to immediately supply information about the civil cases.

Roberts and Douglas Shelley were both booked into the Flagler County Inmate Facility and have since been released on $1,000 bail each.

According to the DEP, illegal dumping is a third-degree felony that could carry a penalty of up to five years in jail, a $5,000 fine or both.

October 26, 2010

BUNNELL — All sludge is not created equal.

There is sludge that is treated as required by law, first at the sewage-treatment plant and then, again, by the companies that haul it away and disperse it on designated sites across the state every day, without incident.

Then there is sludge that violates state law, the kind that was recently dumped on a Bunnell field, straight from the Daytona Beach treatment plant without any secondary treatment. It smells horrible and attracts swarms of flies, “ruining” the lives of nearby residents.

Under-treated sludge also creates conditions ripe for high levels of fecal coliform that could cause “a host of diseases” including E. coli, officials said. And, if a hard rain hits soon after it’s been spread, sludge runoff can contaminate nearby lakes or streams and groundwater.

The illegal dumping — which has happened before and agitated western Flagler County residents for years — led the state Department of Environmental Protection to send a “notice of permit denial” to Shelley’s Environmental Systems of Zellwood earlier this month. The company has until Thursday to file a petition for an administrative hearing or the DEP’s proposed action for denial would become final.

“Then it moves into the court system, and there’s no way to guess-timate how long it will take,” DEP spokeswoman Lisa Kelley said. “Until there’s a ruling, they can conduct business.”

That is, they can conduct business as long as they’re doing it properly, and Kelley said the company would be subject to criminal charges if it dumps under-treated sewage again.

“They, like all facilities, will be monitored closely,” she said.

According to its website, Shelley’s is “the industry leader in ‘biosolids (residuals) management,’ for over 25 years.” The permit denial by the DEP puts cities that contract with them — including Daytona Beach, Ormond Beach and New Smyrna Beach — in the position of possibly needing to find a new company quickly to haul away hundreds of tons of treated sewage each week.

Investigators from the DEP, with help from the state Department of Transportation, followed a Shelley’s truck Sept. 27 from the Daytona Water Treatment Facility on LPGA Boulevard to Cowart Ranch property off County Road 305 in western Flagler County, according to DEP reports. They witnessed Douglas “Bear” Shelley and Scott Matthew Roberts “dumping raw residual waste on spread fields.” Both men were charged with illegal dumping.

“This was not completely untreated waste,” Kelley said. “It was treated at the water-treatment facility, but it’s supposed to be further treated to reduce (fecal) coliform and vector attraction (flies).”

Dale Clegg’s family still has property near the Cowart Ranch, but he no longer lives across the street from where the dumping occurred.

“It was ruining our life,” he said. “The smell and the flies. I really couldn’t understand why they would do this to us.”

Clegg is one of many western Flagler County residents who kept after county and state officials to “do something” to keep the odor under control and the number of flies down. The DEP also found Shelley’s out of compliance in August 2007 and is in court with the company now over several inspection violations found in 2008, including improper discharge.

“I’ve seen them come out (to dump) on Thanksgiving, and then it just sits there piled up,” he said. “And then again on Christmas Eve, I tried to let my little girl enjoy the night and the full moon but had to bring her back inside.”

Done correctly, “bio-solids are the primary organic solid product yielded by municipal wastewater treatment processes that can be beneficially recycled,” according to the Environmental Protection Agency’s regulation documentation, commonly referred to as the “Part 503 rule.”

Lifelong Bunnell resident Blane Taylor said his concern is what happens to the surrounding soils and aquifer when a spread is done incorrectly.

There are “a host of diseases” associated with under-treated waste, according to Benjamin Juengst with the Flagler County Health Department.

“The most common are E. coli, shigella, giardia, cryptosporidium,” he said.

All four can cause severe diahrrea, whether by virus, bacteria, or parasite.

Juengst said runoff is more of a problem than what could possibly seep through the ground to the aquifer because sunshine would kill any viruses spread on the fields. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, though, there are some E. coli organisms that can survive several weeks on countertops and up to a year in materials like compost.

David Shelley, the owner of the company, has not returned repeated News-Journal calls, but Rob Cowart — a member of the family that owns Cowart Ranch — spoke freely.

“We don’t get paid to let them dump on the land,” he said while eating a large midday dinner at a long farm table in his kitchen wallpapered with cowboy boots. “But we don’t have to purchase fertilizer for our land. And, you know we have poor soil here in Florida.”

He doesn’t worry about living on the property — which is a stone’s throw from one of many spread fields — and his nephew Charlie Cowart jokes about playing in the “cake,” as the solid residuals are called.

“Besides,” the older Cowart said, “what are you going to do with it if you can’t put it on the property?”

The Sept. 27 dump in Bunnell was about 25 yards, or 2,000 pounds of partially treated sewage.

“Shelley’s is permitted to produce 283.8 dry tons per day for land application on agricultural sites in accordance with an approved agricultural use plan,” Kelley said.

There are 10 other “residuals management facilities” besides Shelley’s that work in the eight-county Central Florida region of Marion, Lake, Volusia, Seminole, Orange, Brevard, Osceola and Indian River counties. Kelley said there “has been no concern expressed” about whether the other facilities can handle the workload.

According to DEP records, Shelley’s dumps bio-solids it collects from Daytona Beach, Ormond Beach and New Smyrna Beach, as well as from several local RV resorts and motels, at eight sites in Volusia and Flagler counties totaling more than 3,900 acres.

In the past three years, Shelley’s Environmental is the only company of the 11 that serve the Central Florida region that has had violations egregious enough that the DEP had to step in and take action through “formal enforcement,” Kelley said.

Daytona Beach has had a waste-removal contract with Shelley’s since 2004. The company makes three pickups a day, every day, for a total of 323 tons each week at a cost of slightly more than $35 a ton, which adds up to $11,382 per week.

“We have contacted another hauler, Florida Enviro, who has a facility at the Tomoka Landfill, and they have indicated that they could haul, treat and dispose of our sludge on short notice,” Daytona Beach spokeswoman Susan Cerbone said Friday.

Other municipalities also are considering their options.

“We’re uncertain whether it will affect us,” said Ellen Fisher, a spokeswoman with the Utilities Commission of New Smyrna Beach. “We’re a little different because we already treat ours (to a level where it can be directly spread). We are looking at our options, though.”

This was copied from a blog that didn't give attribution to the author.

Take a deep breath at Hank Scott's farm — but be prepared.

The farm, best known for producing the staple attraction at the Zellwood Sweet Corn Festival and a walk-through maze every autumn, uses composted waste from Disney's Animal Kingdom to fertilize its sod fields.

There's no question that it stinks sometimes, said Scott, whose family has farmed there since 1963.

But neighbors within a 4-mile radius of the Long & Scott Farms, who also hold their noses because of odors wafting from the nearby Monterey Mushrooms farm and Shelley's Septic Tanks on Jones Avenue, smell trouble brewing as Scott seeks permission to compost biosolids on 44 acres near the Orange-Lake county line.

The process could save his sod operation about $100,000 a year in fertilizer costs.

His neighbors fear that the biosolids — human waste culled from septic tanks and municipal sewer plants throughout Central Florida — pose health risks from airborne pathogens and other germs lurking in the treated sludge.

"I don't want my neighborhood to be the toilet of Central Florida," said MaryEllen Proctor, a resident of nearby Lake Jem, who spoke out against the farm's plan at a recent zoning-board meeting in Lake County.

The sludge could possibly be radioactive, suggested another neighbor, Susan Klinzing Tobin, an environmental consultant, who wondered about contamination from cancer patients receiving radiation treatments.

'Grasping at straws'

If approved by Lake commissioners next month, the conditional-use permit would allow Shelley's — Scott's partner in the venture — to haul biosolids mixed with wood chips to a back lot at the farm for composting. The compost would be used exclusively to revitalize Scott's sod crop and fallow grass fields.

He said he wouldn't use it on his corn, pickles or other vegetables.

Timothy Talbot, an environmental consultant representing Scott's farm and Shelley's, said the process, which also must be approved by the state Department of Environmental Protection, poses no health dangers.

Talbot said similar operations are used near Disney and at C&C Peat Co. in Okahumpka, a 20-acre composting center where he hopes to arrange tours for skeptics and opponents of Long & Scott's plan.

Talbot said composting at Scott's could reduce foul odors in the neighborhood because Shelley's would rely less on quicklime, a stabilizing agent that kills pathogens in biosolids and converts sewage sludge into usable fertilizer. The quicklime mix releases ammonia and reeks when stirred, often prompting complaints.

Cary Oshins, a spokesman for the U.S. Composting Council, said federal studies that examined dangers associated with commercial composting operations have concluded they pose no increased risk to neighbors.

He dismissed the fear of possible radioactivity, saying "that's grasping at straws."

'A tough business'

Some neighbors say they don't trust Shelley's, describing the Orange County company's history with state environmental regulators as "long and sordid" and pointing to complaints including dumping raw sewage on farmland and failing to adequately control odors at the septic company's operation on Jones Avenue.

Others dread a parade of sludge trucks — perhaps 50 or more a day — rolling through the community.

"I like to start my morning on the porch listening to songbirds," said Deborah Parks, an artist who owns a home on County Road 448A. "I don't want to hear the constant beep-beep of front-end loaders and sludge trucks."

Some neighbors also fear it will harm property values and force them indoors.

David Shelley, who is investing in the plan because of changing regulatory rules that will make it more difficult for him to find sites to spread the odiferous lime-treated sludge, defended his family-owned company's regulatory record, vouched for the safety of the composting process and insisted it would be less offensive.

He predicted the venture would allow him to add jobs and cut fuel costs.

He predicted the venture would allow him to add jobs and cut fuel costs.

"What we do is a tough business," Shelley said. "But it has to be done somehow, someway and somewhere because, when you really think about it, we all contribute to the problem, and there's no end to it."

Comments

Post a Comment